Interview With Multidisciplinary Artist Kelly Nunes

CODAzine is highlighting the public art community to share stories about leading creative professionals and the innovative art they are creating. This series of interviews is presented by SNA Displays.

This month, we feature Kelly Nunes, a creative director and multidisciplinary artist. We asked Kelly a few questions about his creative process, inspirations, and what’s ahead. Here’s what he shared with us.

Kelly Nunes is a creative director and multidisciplinary artist known for immersive, responsive environments that blend light, sound, video, and spatial design to create transformative experiences. Born in Toronto, he is currently based in Montreal, where he has collaborated with studios like Moment Factory and Daily tous les jours.

How did your background in scenic design lead you to become a multi-disciplinary artist?

I appreciate environments that facilitate contemplation and self reflection. I struggle with meditation so any opportunity to sit in an environment that decreases stress and anxiety while facilitating self awareness, sign me up. If I can produce those environments I feel like I’m giving back. And of course I’m doing it for selfish purposes as well. I like spending time in these environments. I typically conceive of a space I would want to spend an extended period of time in.

What does “responsive environment” mean to you, and how do you think it shapes the experience of audiences in your installations?

In my practice, responsive environments are interactive spaces designed to respond to a person’s behaviour in nuanced ways, sometimes imperceptible at first, with an emphasis on drawing people into the experience without making them feel like they are the primary focus or the “user”. The environments I create are immersive and the stories are typically about inclusion in some form, so using interactivity as a means to lure people into an interconnected world, rather than making them the master of it, is a principle that stems from a belief that participating in something “bigger” than our own individual existence is liberating, and may hopefully help folks think more about their relationship to nature, the cosmos, and each other.

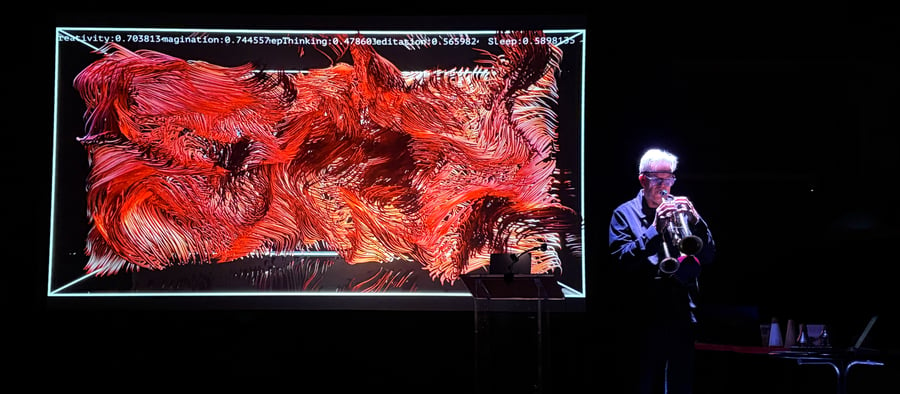

Can you walk us through the concept and creation of NEWT Miami, especially how you synchronized motion graphics with live orchestral music?

NEWT turns ten years old this year, and while Dejha Carrington and I would approach the technical implementation differently today, our commitment to democratizing art in public space has remained constant. At the time, our challenge was synchronizing the soundtrack heard on personal mobile devices with the video visible on the InterContinental Hotel façade—often from viewing distances of up to a mile.

Our solution was to host the soundtrack on a website synchronized to the media server clock driving the hotel’s two 20-story digital façades, which displayed our Newton color-theory video facing Biscayne Bay and downtown Miami so that members of the public streamed the audio directly from the URL on their own devices, allowing the sound to remain in sync with the visuals regardless of location.

For the live performance, we staged the orchestra in the Bayfront Park bandshell and provided the conductor with a click track tempo synchronized to the media server’s clock, delivered through a headset, which the conductor then relayed to the orchestra through his baton, maintaining alignment with the video playing on the building behind them.

Your work sits at the intersection of architecture, scenography, and technology. What are the biggest technical challenges you face when combining those elements?

My aim in combining architecture, scenography, and technology is to blur the boundaries between the three, producing work that is holistic and cohesive—reflecting the sum of these parts rather than their separation. The most rewarding challenges arise in the development of hybrid materials or the novel use of existing ones, where solutions often depend on material R&D with designers, integration into architectural plans with engineering approval, and close collaboration with technologists to embed and conceal technical systems within the physical structure while maintaining service accessibility—all while navigating the inevitable friction that comes from these disciplines speaking different languages and operating within distinct processes.

Technical challenges vary with the ambition of the project, from protecting sensitive systems against extreme environmental conditions (for example, BHX travels in a 53’ semi that may cross a sub-zero mountain pass and enter a 35°C desert on the same day) to ensuring the long-term stability of hybrid materials such as Glacier Cave’s plastic-bottle ice ceiling or the upcycled “paper rock” surfaces in Earth Room, challenges ultimately addressed through rigorous prototyping and stress testing.

In Glacier Cave, you reflect on water, plastic, and climate change. How do you translate these urgent environmental themes into immersive public art?

Glacier Cave was commissioned by Dax Dasilva for Age of Union, his environmental foundation gallery, making clarity of message essential. The installation uses discarded plastic water bottles to construct a pristine glacier ice cave, deliberately highlighting the absurdity of our ongoing dependence on plastic to deliver “clean” water—despite mounting evidence that it contaminates our bodies with microplastics and of course pollutes the world’s oceans. By employing the very material under critique, the work adopts a subversive approach that underscores the contradiction at the heart of modern consumption.The space is interactive, responding to visitor behavior: heightened activity causes the glacier to thaw, crack, and moan, while calmer presence elicits sounds of glacial serenity, transforming the cave into a space of gratitude and acknowledgment of the essential role clean water plays in our lives.

When designing immersive environments, how do you balance creating a sense of wonder with maintaining a coherent narrative or structure in the work?

First I aim to ensure that the narrative is clear to the visitor from the outset. I like that the sense of wonder experienced within the environment is personal and subjective—and somewhat beyond my control—so the intention is that clear narrative signifiers combined with will invite that wonder to surface and permeate the space..

Your projects range from massive public façades (like NEWT) to intimate, enclosed rooms (like the Moon Room). How does scale influence your design decisions?.

With NEWT, the objective was to translate the monumental, city-scale experience of a massive media façade into an intimate, human-scale encounter—using sound delivered through personal devices while viewers watched a 34-story building perform from up to a mile away. The Moon Room approached scale in the opposite direction: visitors stood just feet from the “Moon,” creating intimacy through proximity, while the scenography treatment created the illusion that simultaneously positioned it as a celestial body thousands of miles away, suspended within the vastness of space.

Your projects often include teams — composers, motion designers, architects. How do you manage creative collaboration, and what does your ideal team look like?

I manage creative collaborations through open dialogue—asking questions, fostering transparency, and ensuring that all contributors feel heard and valued. My ideal teams include creative technologists, video designers, software developers, industrial designers, architects, sound designers, and mix engineers, each bringing distinct expertise; however, a shared, solution-oriented mindset is essential, particularly when navigating complex challenges or adversity

Do you prefer working in public spaces (like cityscapes) or in more controlled environments (like galleries or dedicated rooms)? Why?

Public spaces are often perceived as being rife with unforeseen variables absent from controlled environments, leading to the assumption that galleries or dedicated rooms offer greater control. In practice, however, those controlled settings are frequently pushed to their limits, presenting challenges that can exceed those encountered in public space. I value the ideas that emerge—however begrudgingly—from constraints that refuse to yield, whether in public settings or within the gallery.

What do you hope people take away from your installations?

I hope people find peace and comfort within themselves, and experience some respite from their everyday anxieties. Each installation carries its own themes and narratives, but I do not expect—or require—those narratives to resonate with everyone. What matters most is that visitors feel better leaving than they did upon arrival; if insights or lessons emerge, that is welcome, but I am careful not to patronize by spoon-feeding meaning or exerting control through overly prescriptive frameworks, trusting that people will arrive at their own conclusions.

In what ways does the physics and spirituality of black holes intersect in the design of the Black Hole Experience?

The Black Hole Experience travels in a double-expandable 53-foot semi-trailer that deploys into a 1,000-square-foot environment, imposing a range of physical constraints. To evoke a sense of infinite vastness and mystery, the circulation path was designed to weave through the space in a way that subtly disorients and plays with the visitor’s sense of direction, while light-absorbing surfaces, shadow, and curved corners—combined with projectors, lighting, and mirrors—create the illusion of infinite depth. These illusions create conditions that can give rise to a sense of spiritual awakening.

More from CODAzine

Subscribe to CODAzine

New from CODAzine

200 Pages of Public Art Data, Insights and Stories

Related Posts

Water as a Medium: Sculpting the Living Element